We had a day dedicated to commemorating Dr. Seuss in my school in India. As a kid, I was never taught to read any deeper into Seuss’ books. However, it’s unsurprising that Dr. Seuss portrayed anti-Asian stereotypes, especially given the mounting tensions of the 1930s and onward. The Japanese aggression in the years preceding World War II—more specifically in Shandong, Manchuria, and Korea—provoked this hatefulness. However, this was also part of an ingrained xenophobia and racism towards Japanese immigrants’ after their first arrivals in the US in the late 1800s, evident from the Immigration Act of 1924, which deemed prospective Japanese immigrants ineligible for U.S. citizenship.

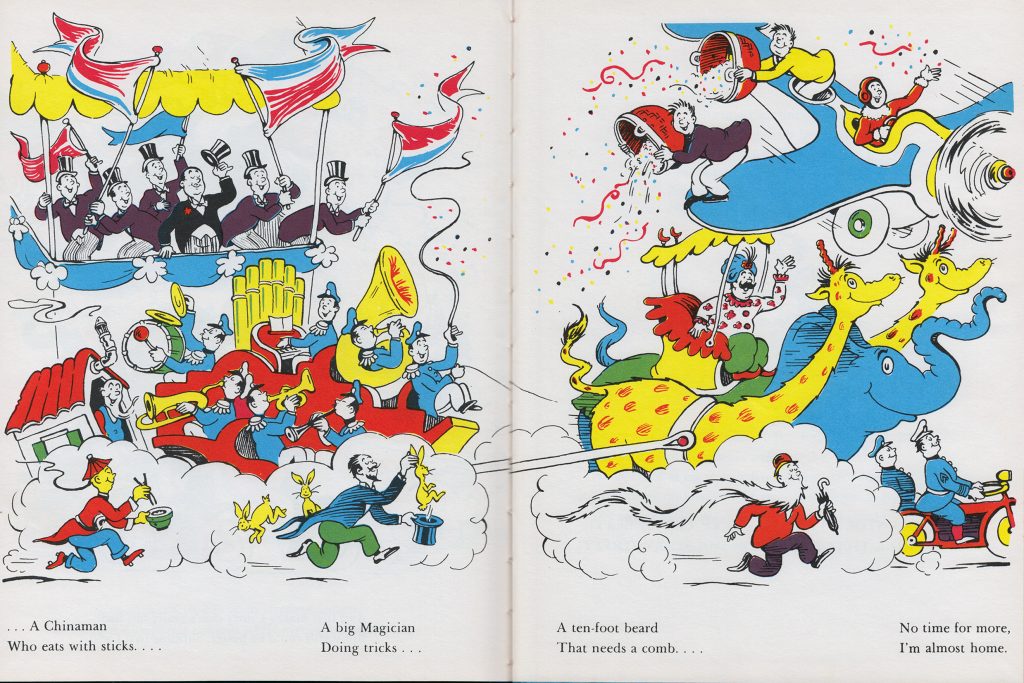

Additionally, Seuss’s racist “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” was published in the same year the Sino-Japanese War broke out (1937). The depictions of the Japanese were accepted and even seen as innocuous because Japan endangered the United States’ economic interests in China. The signing of the Tripartite Pact (Germany, Italy, and Japan) associated the Japanese with the horrendous actions of Germany and fascist Italy. With the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, anti-Japanese sentiment exploded. Not addressing this ugly history of xenophobia makes us less cognizant when stamping out modern-day racism. These issues have persisted for decades upon decades.

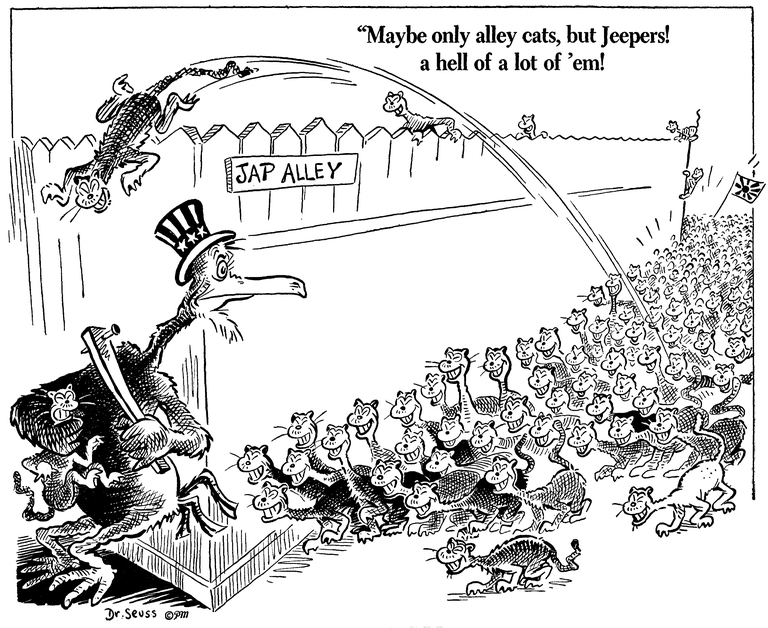

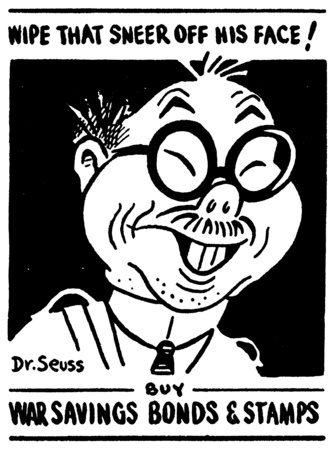

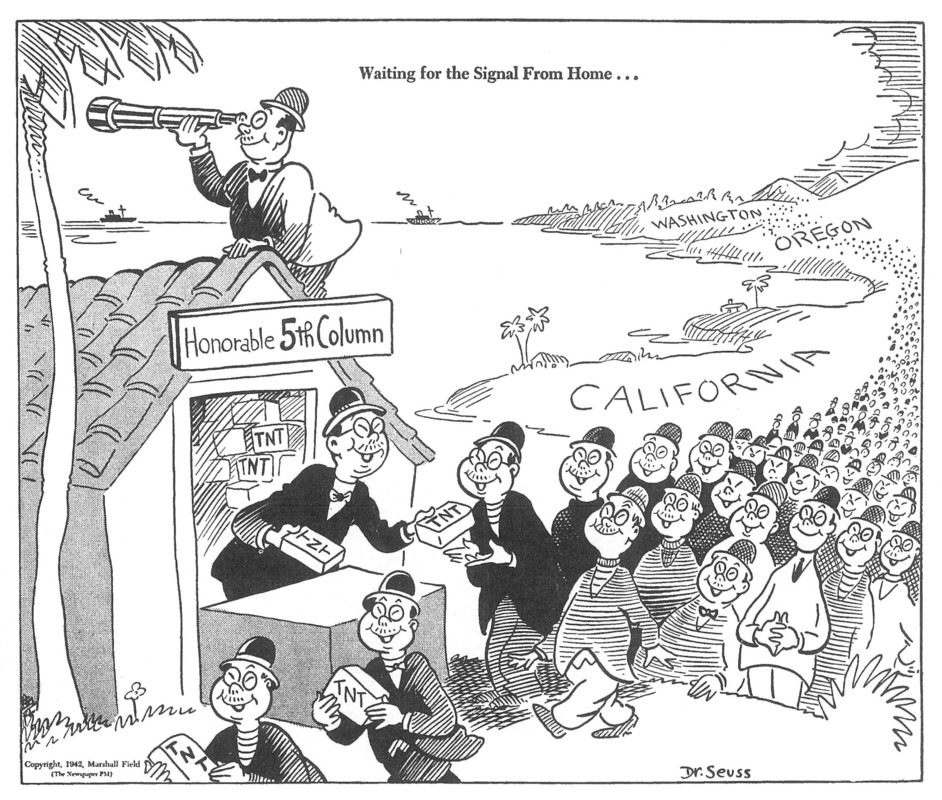

Seuss’s depiction of the Japanese and animosity toward isolationists such as Charles Lindbergh, a pilot and prominent public figure, were almost a “cultural preparedness” against Japanese immigrants and American-born individuals of Japanese descent, akin to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s military preparedness for the war.

Dr. Seuss did not harbor the same prejudices toward African Americans and Jews. It is also pertinent to consider that Dr. Seuss was the grandson of German immigrants.

In a twisted way, the internment of innocent Japanese American’s was perceived as justifiable and a preventative measure should they plot against the US from within (“Waiting for a signal from home”).

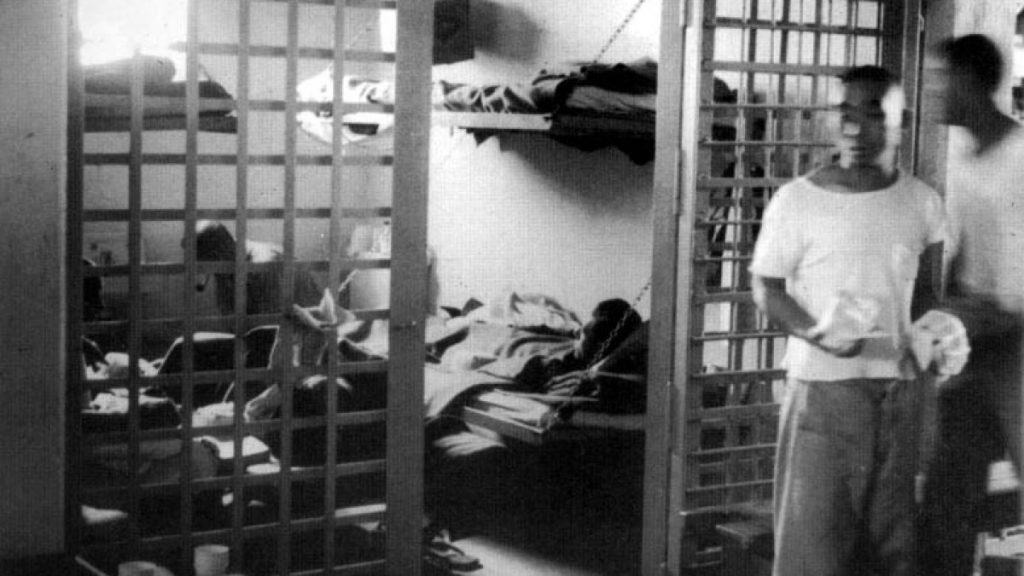

Executive Order 9066 forcibly placed 117,000 Japanese Americans and residents in “relocation centers.” The War Relocation Authority enacted this order, displacing anyone who was “at least 1/16 Japanese.” In the Tule Lake segregation camp (pictured below)—designated for uncooperative internees—a violent riot erupted in 1943. Similar such events took place and were violently subdued with tear gas, guns, and beatings because of overcrowding, hunger, and general resentment.

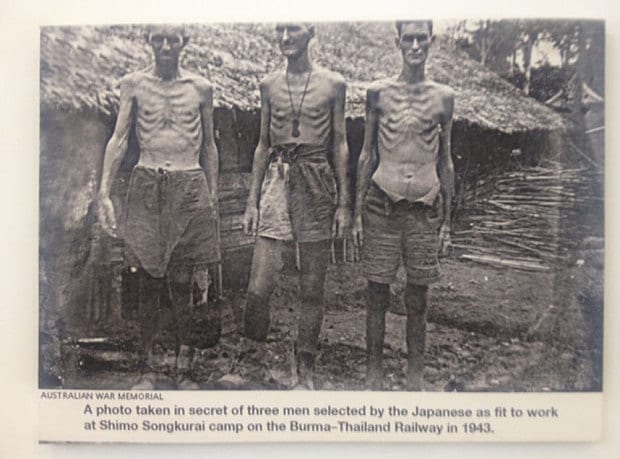

Conversely, the horrific events surrounding the Bridge over the River Kwai, colloquially called the Death Railway, reveal the inhumane treatment that an estimated 140,000 Allied prisoners of war (POWs) were subjected to by the Japanese Railway Regiment. The 1946 Tokyo Tribunal reports that the mortality rate was a staggering 27.1% in these construction camps.

Was Seuss a “man of his time?” It’s hard to reconcile Seuss’s racism with the contributions to literature and education he made. One should not eclipse the other. He condemned anti-semitism in “The Sneetches” and promoted the conservation of the environment in the beloved book “The Lorax.” Are we going to forget all that? Moreover, Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ choice to pull select titles from print (And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the ZooMcElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super! And The Cat’s Quizzer) is a clear instance of whitewashing history. It’s a sad reality that children are faced with racism, but redacting its existence has a paradoxical effect. Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ decision ensures that the evidence of Seuss’s racism will only exist in articles and perhaps museums, having the effect of altering history to paint a prettier picture. Instead, we should teach children better and more truthfully, using the ugly realities of Seuss’s books as an example.

Sanjna Rajagopalan

Opinion Columnist

Graphic: “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” – Dr. Seuss