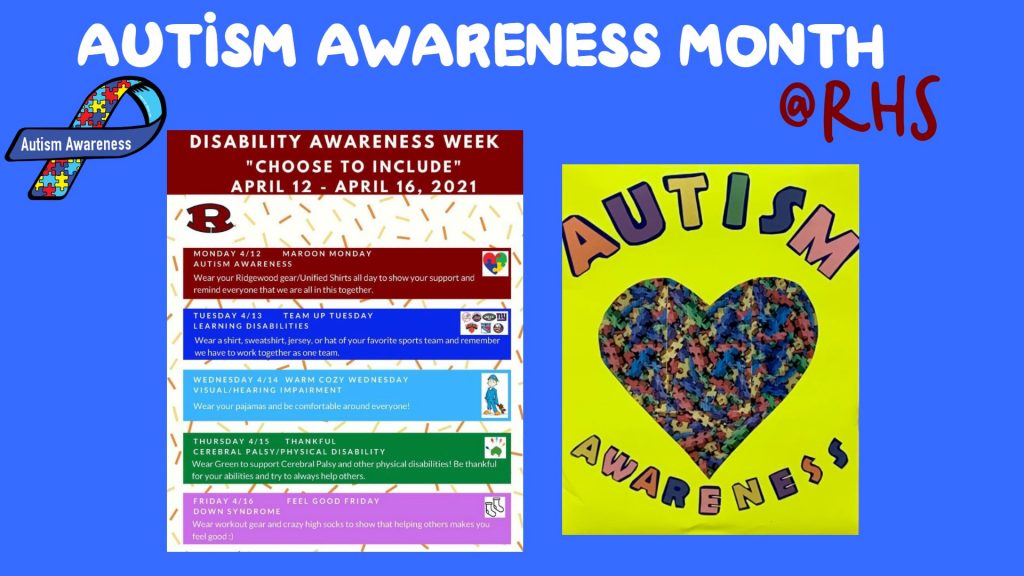

April 2 was World Autism Awareness Day and April is Autism Awareness Month. During this month, it’s encouraged that everyone wears blue to promote autism awareness and to show support to those families with autism. Thereby, RHS’s Social Skills Volunteering Team is now organizing an event to work with autistic students in Ridgewood in July. Autism is a complex developmental disorder. It is a result of a neurological malformation which affects the normal functioning of the brain. It’s usually detectable in the first 3 years of life. Because of the unusual body language of people with autism, people who don’t have autism may have a hard time communicating with those who do. Autistic people hereby experience difficulties with social interaction and communication, and suffer loneliness.

Humans chiefly have 6 emotions: happiness, sadness, surprise, anger, fear and disgust. The ability to express and understand these emotions starts developing at birth. At around two months, most babies will laugh and show signs of fear. By 12 months, healthy babies can read your face to get an understanding of what you’re feeling. Most toddlers and young children start to use words to express feelings. Throughout childhood they build skills to manage their emotions and recognize and respond to other people’s feelings. They continue building empathy in this time period and by adulthood, people are usually able to recognize subtle feelings, such as surprise and disgust, and their construction of empathy is finally complete. It takes a longer time, however, for autistic children to start expressing and reading emotions. Autistic people have trouble interpreting emotions – both that of their own and others. At the age of 5-7, they are capable of differentiating between happy and sad, but the differentiation of fear and anger might still give them a hard time. In their teenage years autistic people still aren’t as good at distinguishing between surprise and disgust. As adults, many still continue having trouble recognizing some emotions, and thereby their empathy capability is limited to a degree.

Since people with autism experience difficulties with comprehending feelings, they inherently also have trouble recognizing and interpreting emotional and social cues, such as facial expressions, voice tone, and body language. Because of this, they not only can’t find a way to manifest their emotions so that other people can have an idea of what they’re thinking and feeling, but they also do not have or rarely have empathy. Autistic people may herewith engage in repetitive behavior, called “stimming”, to compensate for their lack of body language and gestures. This is also how they concentrate. These may include: rocking their body, flapping their hands, spinning etc. Because of all of these missing or scant communication skills, people who aren’t autistic indicate that they feel like they are trying to communicate with a person who doesn’t speak their language or the person they are talking to is in complete apathy when talking to an autistic person.

The world is based on exclusion. This system, governments, schools – everything’s runs on this corrupted mentality. People tend to categorize and try to prove the differences between abilities/disabilities, ethnicities, nations, sexual orientations and much more just for the sake of science, but not for celebrating these variations and trying to better understand what a specific group of people may be experiencing and what difficulty that specific group might be going though differently than others. People blindly assume that an autistic person doesn’t want to engage in conversations. They look at how much stimming looks bizarre to them and amuse themselves with it, or even find it creepy. And they find the solution to this problem by simply avoiding them or not trying to understand them. The apathy your autistic friend might seem to be demonstrating doesn’t mean that they don’t want the conversation, the help, or the social interaction. Therefore, we shouldn’t ignore them and avoid attempting to have empathy for them. In fact, we should have twice as much empathy for them than for people who don’t have autism to compensate for the lack of empathy they have. To communicate with autistic people, we can label emotions verbally, instead of expecting them to interpret social cues. We can tell them what they must be feeling according to the context. For example, telling them how sad or happy they must be feeling at the moment, since feeling something and not being able to convey it must be difficult. We should also articulate what we feel instead of just smiling, making a face, or crying. When talking to them, we can also put lots of emotions and exaggerate our feelings via our voice tone and facial expressions for them to better understand us.

Trying to understand autistic people and trying to communicate with them isn’t hard at all. We can make this group of people’s lives better and make them feel more understood and wanted. We do that by understanding that not everyone has the talent to understand others, lack of empathy isn’t something to get frustrated by at all, and paraphrase sentences in a way which is easier for people with autism to comprehend.

Elijah Otaner

Staff Writer

Graphic: Sunny Rhew