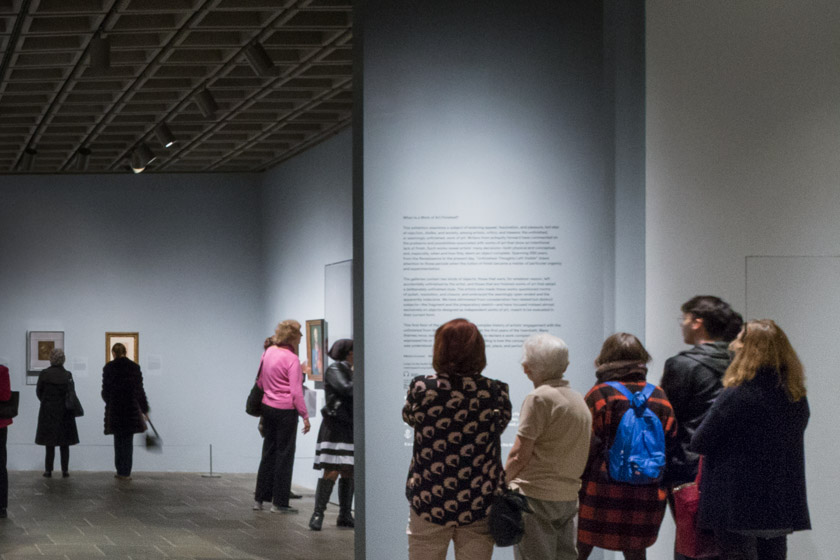

After visiting the exhibit, ‘Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy,’ at the Met Breuer in NYC, I have a much better understanding on how art affects people in the strangest ways. Art exists not only to create something that is appealing or to make something that everyone will enjoy. A part of art is the bravery of putting out something you fully believe in, maybe if it even diminishes something else. The exhibit I just visited holds so many opinions on things that have ran through our world’s history, so many viewers who are not afraid to let their creativity take charge. Art connects its viewer to his or her senses, very often swaying its patron into agreement with what he sees before him. Artists often use their voices through their work, connecting society, politics, and ethics, through a range of differing ideas and perceptions to spur thought and action in its viewers.

The messages that are told through art show how important it is to our society. In the exhibition “Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy” at the Met Breuer, its purpose was to explain how art portrays these messages and how the audience is affected by them. The Wall Street Journal writes, “Fears of a ‘deep state’ and corporate malevolence… ‘Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy’ at the Met Breuer purports to be the first major exhibition to trace this electrifying theme in painting, sculpture, photography, video and installation art.” The exhibit features 70 works of art from 30 different artists.

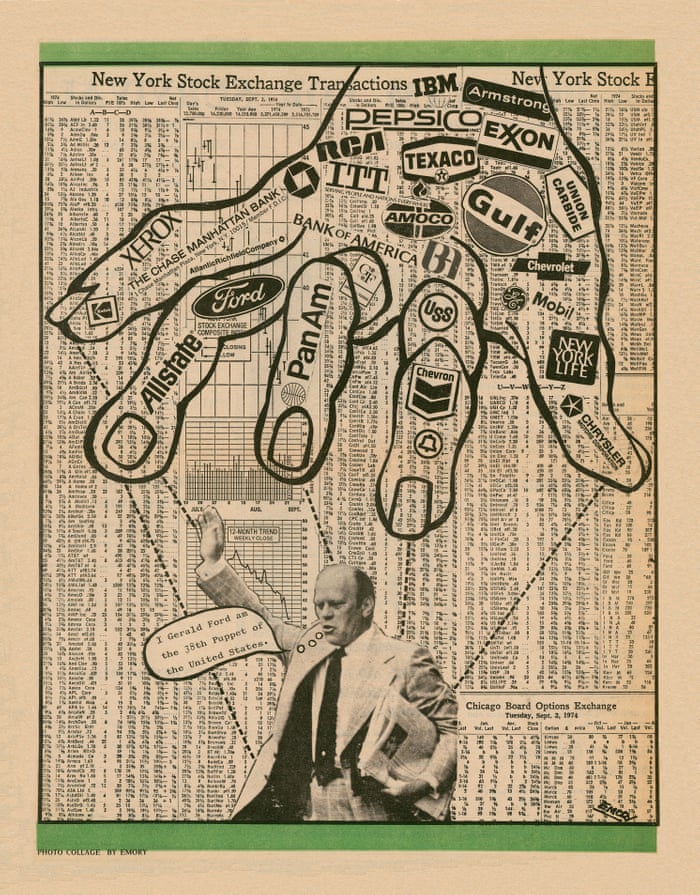

The art pieces within the exhibit brings back many controversial points in history, beginning in the 1960’s and going right into present day; these political arguments have served as propaganda for many decades and it is continuing to occur. There was one piece in particular, that even if it was made 50 years ago, the message could be relevant today. An illustration of The Black Panther by Emory Douglas shows a large hand with many brands in it, holding the 38th president Gerald Ford like a marionette. In analysis, these brands, the largest at the time, controlled the president like a hand to a puppet, having authority over the president. It is not difficult to see how this relates to the present day, especially with regard to other countries and our government.

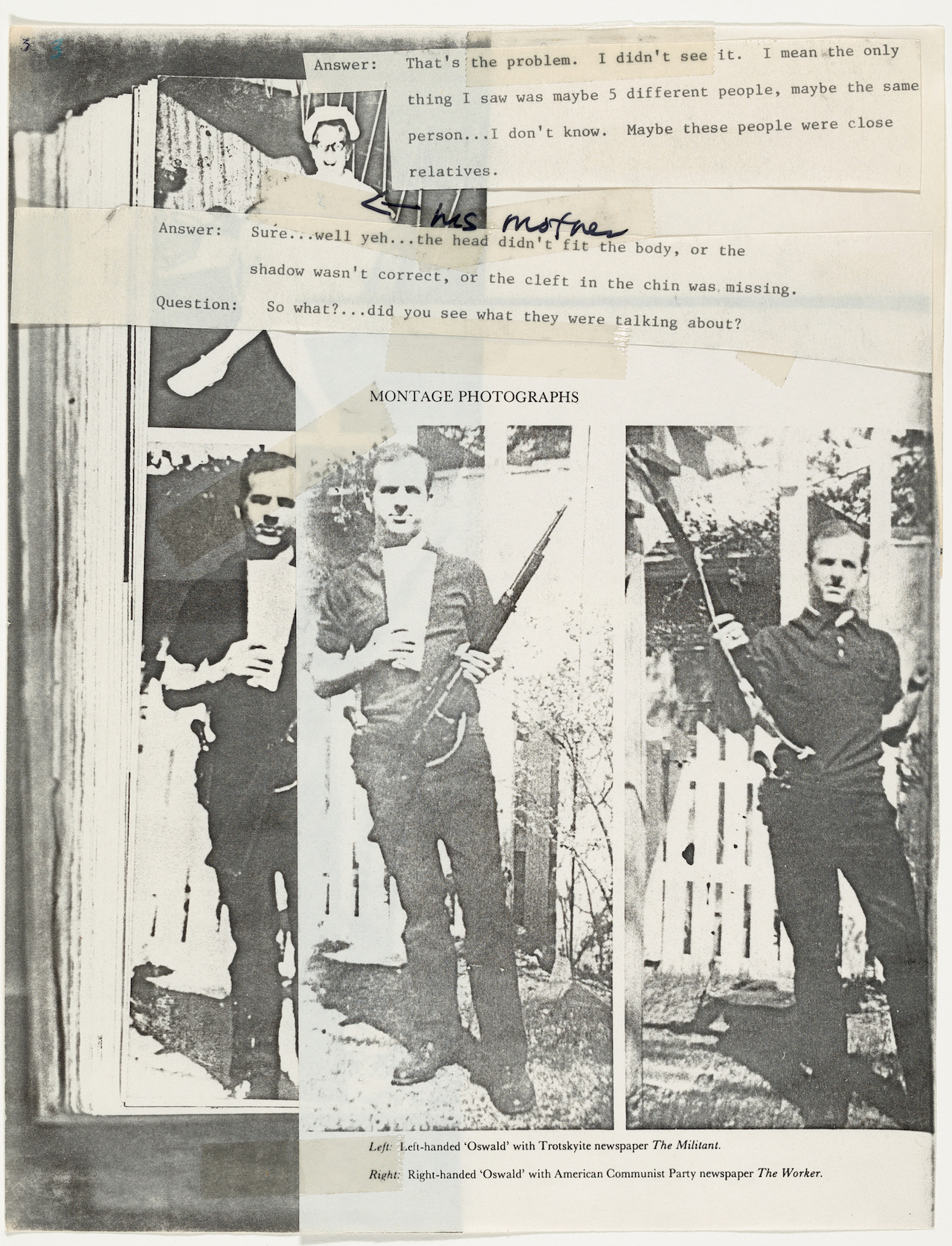

Another eye-catching piece was “The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview” by Lutz Batcher. Instead of an actual interview, it is, in reality, an 18-piece collage of Batcher interrogating herself about the possible murderer of John F. Kennedy. The way that she approaches this is almost manic, having a two-person conversation with herself in a forceful tone. A couple of clips of the collage state, “Answer: I didn’t see it. The only thing I saw was maybe 5 different people, maybe the same person…Question: So what?…did you see what they were talking about?”

These dramatic events do not only involve the victims and suspects- they involve everyone that is involved, even if they just see it on TV. These events impact millions of people, which explains how the aftermath can last forever. Some of these people choose to communicate their expressions through art because this way, they know they are not the only ones affected by these incidents, and the artists can be stronger together than them being separate.

Conspiracy theories are beliefs that question the conventional “truths” explaining certain events. Merriam-Webster Dictionary states that a conspiracy theory is “a theory that explains an event or set of circumstances as the result of a secret plot by usually powerful conspirators.” By using the word “secret plot,” this might suggest how conspiracy theories might not be as obvious as the accepted story, which suggests that they’re more controversial. These theories come from people in dire need of a change, especially in the political sense. Within much of the exhibit lies a (not so) hidden meaning of refusal. One piece by Mike Kelly, an avid conspiracy theorist, illustrates an entangled, messy blob of random things in the government. With a closer look, you can see the chaos happening in the blob, which Kelly himself calls a “garbage drawing.” This entanglement is a hairball being pulled out of a bathtub drain, a blockage in the drain, something that someone needs to get rid of.

These dramatic events do not only involve the victims and suspects- they involve everyone that is connected, even if it is just seen on TV. These events impact millions of people, and the aftermath can last forever. Some of these people choose to communicate their expressions through art because this way, they know they are not the only ones affected by these incidents and can unite with other artists that hold the same feelings. Now looking at it, everything is basically connected. Making your own beliefs and showcasing them is art, something that you made, something original that the world has never thought of in that way. And vise versa– art is a theory; It is a theory that you believe in, an idea that expresses an opinion. This experience has made an impact on what I thought was important in art, shining a light on the different parts that get less attention. How these two types of art correlate proves how everything really is connected.

Jacob Baskin

staff writer

Graphics: courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brett Beyer, Emory Douglas, Lutz Bacher, Mike Kelly