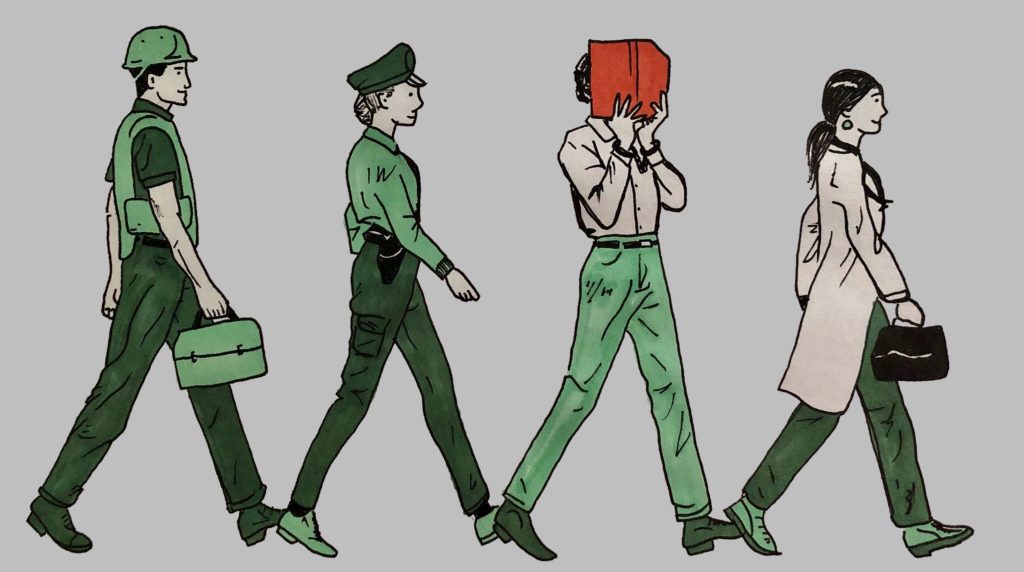

Close your eyes and picture a criminal. What do you see? Probably a dark, shadowy figure with a malicious snarl and a glinting knife. Chances are, you don’t see a well-dressed businessman with a charming smile and a firm handshake.

As this indicates, our perception of crime is heavily skewed towards the lower classes of society, the more visible and the less powerful. In reality, however, white collar crime is much more prevalent and damaging than we give it credit for. According to the FBI, white collar crime costs the US more than $300 billion annually — money that could be spent towards welfare, education, or infrastructure. The FBI predicts that “losses due to fraudulent activity approached 10% of the amount of money that we expend in healthcare.” Despite this, we still don’t treat many of these white collar-criminals as criminals at all. While our prisons fill up with low-level blue-collar offenders, the upper-class market masterminds generally walk away scott free.

In a clear example of this, just a few months ago, Donald Trump’s campaign chairman Paul Manafort received an initial sentence of only 47 months in prison on charges of bank fraud, fake tax returns, and failure to report foreign assets. Scott Hechinger, a senior attorney at the Brooklyn Defender Services who advocates on behalf of those who cannot afford legal representation, responded that one of his clients was offered a similar sentence merely for “stealing $100 worth of quarters.”

Though Manafort’s prison sentence was eventually raised to 7.5 years, it still falls short of the suggested range of 19.5 to 24 years in prison. Not surprisingly then, a 2017 study by the University of Iowa reported that federal judges in white-collar cases, “frequently sentence well below the fraud guideline,” and follow the advisory guideline in less than half of all cases. In stark contrast, many blue-collar criminals come up against the harsh and sweeping mandatory minimum laws, which allow no leniency for nonviolent drug offenders in imposing a minimum sentence of five years.

Why the disparity in treatment?

A large reason is our popular culture, which glorifies white-collar crime in a way that makes it acceptable and even fascinating to the general public. TV series such as White Collar and movies such as The Wolf of Wall Street romanticize the glamour of high-profile crime. The term “con man” itself comes from a New York Herald report of the 1800s that dubbed property thief William Thompson as “the Confidence Man.” Clearly, we give much attention to high-profile criminals, but not the right kind of attention.

While white-collar crime seems harmless, it has very direct and damaging effects on the public. One of the greatest examples of these disastrous consequences is the 2009 Recession. The predatory lending practices that resulted in the housing market crash also led to the loss of 8.7 million jobs in the US and were linked to over 10,000 suicides across North America and Europe, according to CBS. Despite these tangible repercussions, not a single top officer from any major bank went to prison.

It’s easy to forget about these cases as they fade from prominence, but now we’re forgetting at a faster rate than ever. According to the New York Times, white-collar cases have only made up about “one-tenth of the Justice Department’s cases in recent years, compared with one-fifth in the early 1990s.” Additionally, law enforcement agencies under the current administration have greatly cut back on prosecution. During Trump’s first year in office, “the Justice Department’s fines against companies fell 90% from what they were in Obama’s last year in office.”

Our justice system needs to change, and this begins with a change in our perception of crime. If we’re going to hold all people equally accountable for criminal behavior, we’re going to need to rethink our definition of “criminal.”

Swathi Kella

editor in chief

Graphic: Evie Cullen